Water justice is not just about changing the distribution of water access and benefits, but access to making and enforcing the governing rules too.

The human right to water is a challenge globally and even here in the Great Lakes too. In recent years, the struggle for clean and affordable water has risen in Flint, Detroit, and in over 100 First Nations across Canada. This post presents 2 examples of how Indigenous nations are taking back some control over how the waters are governed. Neither of these initiatives are currently operating in the Great Lakes, but add your comments on whether or not you think they could be and how. (Update: 3rd example now linked in the comments section. Let's all add more to learn from).

The first one comes from Atlantic Canada -- the provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. While most people in these places have clean and affordable tap water, 3 out of the 30 First Nations in this region do not.

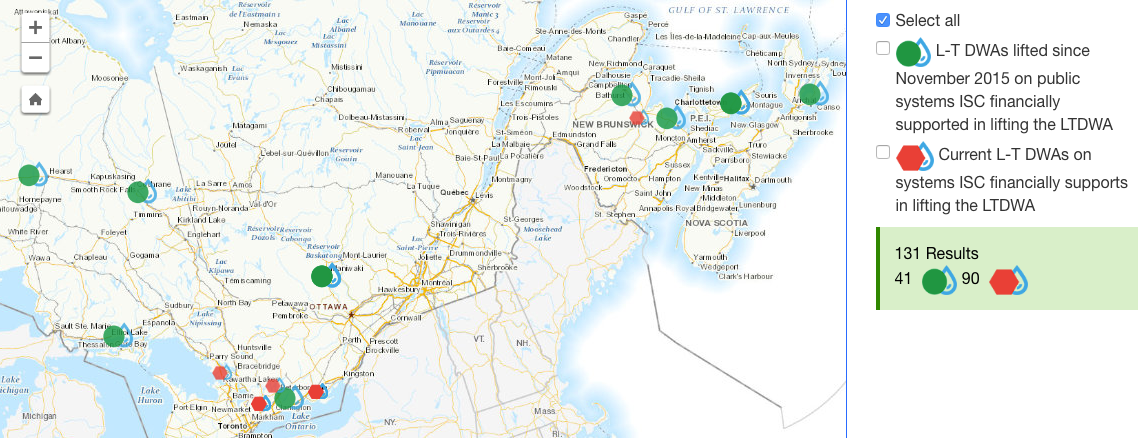

There are 634 Federally recognized First Nations within the borders of Canada -- a state (not a nation) made through partnership Treaties and outright land grabs. According to the Federal government, there are currently 90 drinking water advisories (DWA) in these First Nations.

The following map shows the DWAs in the Great Lakes and Atlantic regions of Canada.

So what could an Indigenous-led water authority look like to end these DWAs that includes boil water advisories, do not consume advisories, and do not use advisories?

From the Atlantic Policy Congress of First Nations Chiefs Secretariat:

Through the vision and leadership of the Atlantic Chiefs, the concept of the First Nations Clean Water Initiative, and by extension, an Atlantic First Nations Water Authority (AFNWA) was born in 2009. This initiative included developing governance structures for the Atlantic First Nations Water Authority, determine financing models, and researching and developing drinking water and wastewater regulations. Furthermore, the Water Authority plans be a First Nation organization, constructed, owned and operated by First Nations. The Water Authority will not be a political organization, rather, it will be a progressive utility focused on the provision of water and wastewater services. Concurrent with the work over the last 8 years, the team has also focused priority around ensuring widespread support from a majority of the First Nations communities throughout the region.

APC Co-Chair, Chief Candice Paul, provided an overview of the Chiefs’ role in developing an Atlantic First Nations Water Authority, and the history of the Initiative. Chief Paul spoke about the benefits of the project, stating, “The most apparent benefit to Atlantic First Nations with the establishment of a pan-Atlantic Water Authority is increased public health and safety with the improvement in quality of drinking water and wastewater” and that “if we work in partnership with a true nation-to-nation approach, we can achieve our goals.”

Water Canada writes:

In 2017, the Atlantic Policy Congress of First Nations Chiefs Secretariat (APC) put forward specific recommendations for an Indigenous-led water authority that would act as a hub to support First Nations communities managing their small water systems. The decentralized, full-service model would incorporate Two-Eyed seeing—traditional knowledge, recognizing that water has a spirit and western knowledge of water treatment. With the plan in hand, the APC is calling on the federal government for the resources to launch it.

“This should be a water authority by First Nations for First Nations,” said Carl Yates, the general manager of Halifax Water. “It is very important to build capacity, to take ownership and chart their destiny through their own advancement of knowledge and operational expertise.”

As of 2018 there are still no regional or national regulations in place, despite the panel’s recommendations and the government’s commitment to pursue them. But the APC’s work on the issue has moved forward.

For the 30 First Nations in Atlantic Canada, the CBC writes:

"The focus of the water authority would be to get the money to invest and bring all the communities to a common standard across Atlantic Canada," said John Paul, the executive director of the organization.

He hopes to have that finished by April 2018. Paul believes the regional water authority is an idea that could help Indigenous communities in other parts of the country. "It could be replicated anywhere else in Canada," he said.

So what do you think? Is this form of Indigenous water governance addressing the short and long term needs for these 30 First Nations? Are there spin-off consequences (good or bad) from having this Water Authority? Let us know in the comments. Now to our next example.

Paying attention to language is an important signal about our relationship to water. Are we stewards? stakeholders? citizens? environmentalists? What about guardians? We've written about Guardianship before, so let's just introduce the National Indigenous Guardians Network initiated by the Indigenous Leadership Initiative (ILI).

The ILI is dedicated to facilitating the strengthening of Indigenous nationhood for the fulfillment of the Indigenous cultural responsibility to our lands, the emergence of new generations of Indigenous leaders, and helping communities develop the skills and capacity that they will need as they continue to become fully respected and equally treated partners in Canada’s system of governance and its economic and social growth. (source)

Indigenous-led Guardians programs empower communities to manage ancestral lands according to traditional laws and values.

Guardians are employed as the “eyes on the ground” in Indigenous territories. They monitor ecological health, maintain cultural sites and protect sensitive areas and species. They play a vital role in creating land-use and marine-use plans. And they promote intergenerational sharing of Indigenous knowledge—helping train the next generation of educators, ministers and nation builders.

There are about 30 communities now in this network, mostly in western Canada. An interactive map helps navigate the growing network.

There is a robust 16 part Guardian Toolkit supporting the development and implementation of this work with the option to upload additional resources.

“Indigenous Guardians programs strengthen our communities,” said Valérie Courtois, the director of the Indigenous Leadership Initiative. “They create jobs, lower crime rates and improve public health. But most importantly, they inspire our young people. They connect them to the land and their elders. They give them professional training tied to their language and culture. That offers hope that can combat the despair so many Indigenous youth feel today.”

Douglas Neasloss, chief councillor of the Kitasoo/Xaixais Nation on British Columbia’s Central Coast, recalls conditions in his nation’s territory some two decades.

“We saw so many illegal activities,” he says. “Everything from illegal poaching of abalone — which was our food that was wiped out almost 20 years ago — to illegal forestry, to a lot of different types of illegal fisheries, to illegal hunting.”

Yet Neasloss says they would only see BC Parks once or twice in a “good year,” and the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans even less than that. The Great Bear Rainforest spans over 100,000 square kilometres — with his nation’s ancestral territory making up some 5,000 square kilometres of that — which means that vast areas were effectively unmonitored.

That’s where the idea of the “guardian watchmen” came in, following the lead of the Innu in Labrador, which first established a program in the early 1990s.

In addition to monitoring for illegal activities, Indigenous guardians serve as ambassadors to visitors, welcoming them to the territory and teaching them about its history and laws.

The Federal government recently committed to spend $25 million over 5 years to seed funding for this network, however it falls short (only 5%) of what is needed for the goal of 1,600 Guardians and associated costs to run this network coast to coast to coast.

But there’s a major problem that has yet to be resolved: the Canadian government still doesn’t recognize the Indigenous laws that guardian watchman attempt to enforce as legitimate. In addition, the federal government has approved a series of resource extraction projects in recent months that challenge Indigenous claims to nationhood, including the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain pipeline and Pacific Northwest LNG export terminal.

Douglas Neasloss, chief councillor of the Kitasoo/Xaixais Nation in this same article says:

“In the eyes of the nation, my community, we feel our watchmen do have the enforcement authority on behalf of our nation. Our nation never signed a treaty with Canada, we never surrendered it, we were never conquered in war, therefore we maintain it belongs to us. The feds and the province do not agree or support that at this point.”

However, he says that while he thinks it’s hard for the Crown to look at relinquishing any authority, the new funding represents a “step in the right direction.”

Check out the video introducing the project:

What do you think? Can these projects be adapted and extended to the Great Lakes? What about Indigenous authorities occupied within the borders of the USA? What are the strengths and weaknesses of these projects? How are they affirming Indigenous nationhood and governance -- in particular, to the roles of women in water protection?

The Atlantic First Nations Water Authority will be an independent organization delivering drinking water, but still reliant on the Federal government for funding. There is power in unity with the Authority carrying the concerns of 30 Atlantic First Nations and a mandate to negotiate and consolidate their collective power.

The Guardians network empowers Indigenous elders and youth to use their experience and ancestral ties to protect the lands, waters, and non-human life for everyone. Rather than more non-native park wardens and conservation officers, authority is grounded in kinship connections and commitments to place. But who's network is it? How can it be a Canadian 'national program' when it is affirming Indigenous nationhood? How far does Indigenous Guardian authority go when it conflicts with Canada's authority and its nested territories, provinces, and municipalities?

Water can show us the way.